CSE6242 / CX4242, Spring 2020

Data and Visual Analytics

Georgia Tech, College of Computing

Project

Grading & Schedule

- Proposal (7.5% of course grade)

- Proposal presentation (5%)

- Progress report (5%)

- Final poster presentation (7.5%)

- Final report (25%)

For example, suppose the final report requires README.txt and report.pdf; if your team submit README.doc and report.doc, 10% will be deducted from the final report's score.

Teaming Important!

The work will be carried out in teams of 4-6 persons.A team may consist of both on-campus and distance learning students (Q section). All such teams will have 3-day lag for all their deliverables. For proposal presentation and final presentation, those teams can choose to do that in class (physically) or submit videos (see details below).

We will grade grad projects and undergrad projects separately; we generally expect grad projects to include more detailed analysis, comprehensive results, etc.

I recommend each group to consist of either all grads or all undergrads. The main reason is that grads and undergrads have different expectations and work schedules. If you want to form a group with both grads and undergrads:

- We will grade that group as if all members are grad students

- Every member MUST fully understand the potential challenges in coordinating work schedules (e.g., grads usually take class on TH, undergrads on MWF) and expectations (e.g., course grades are generally very important for undergrads)

The main reasons are: (1) most large-scale data analysis projects in industry are team-based; (2) many former students found the projects highly beneficial to them. If you strongly desire doing solo projects, this course unfortunately is not a good fit for you.

Some students mistakenly believe that the group projects reduce the amount of work that needs to be graded. Any instructors or TAs know that open-ended questions, and in this case projects with topics chosen by students, need a lot of thinking and time from the graders' end. In fact, open-topic group project is one of the hardest thing to scale to large classes. I thought hard about whether to remove it and do exams instead, which could have really saved us a lot of our time (TAs and myself)! I decided to keep the group project because of its benefits.

Choosing a Topic

Pick your own topic:

- You need to justify that the topic is interesting, relevant to the course, of suitable difficulty.

- Required components:

- at least one large, real dataset;

- some non-trivial analysis/algorithms/computation performed on the dataset (e.g., computing basic statistics, like average, min/max will not be enough); and

- an interactive user interface that interact with the algorithms (can be visual, voice-controlled, on tablet, desktop, etc.).

Harder way:

- Joint projects with other courses might be negotiable. You must obtain the instructor's approval, and you need to clarify exactly what will be done for this course that is on top of and different from what you will do for the other course.

- Projects related to your dissertation/master-project are also possible, as long as there is no 'double-dipping', i.e., you clearly specify what the project will do, in addition to what you were planning to do for your thesis anyway.

Once you have selected a topic, you should do some background reading so that you are capable of describing, in some detail, what you expect to accomplish. For example, if you decide that you want to implement some new proposal for a multidimensional file structure, you will have to carefully read the paper that proposes similar structures, pinpoint their weaknesses, and explain how your approach will address these weaknesses. Once you have read up on your topic, you will be ready to write your proposal.

There are quite a few ways to define "large". It can be measured in size on disk, number of rows in a database, number of edges in a network, etc. One person's "large" could be another person's "small". For example, in my research group, we routinely work with million-edge graphs (say, just working with the graph structure; you’ll work on such “large” graphs in HW3 using just your computer), which are considered "small" in the data mining community, but large in other communities and applications. If you're working with videos, a few million of them will take up terabytes of petabytes. For those of you working in industry, you likely would routinely work with datasets that are in terabytes or petabytes.

The main reason for requiring the use of a large dataset is so that you will learn to handle non-trivial computing and visualization problems. So the larger the better. The harder the problem, the more thinking you will need to do, and the more you will learn.

If you can run an algorithm or analysis on your computer and get the results in a few seconds, your dataset is likely too small (and you likely won’t learn much from this experience). Similarly, if you can plot every single data point on the screen trivially and that doesn’t create any visual complexity or interaction challenges, your data is also likely too small. In other words, you should “suffer” a little when analyzing the dataset, so that you would think about what the challenges are and how to tackle them!

If you have a large dataset and that makes the project too hard, you can always choose to work on a subset of it. But if your dataset is too small (e.g., a few hundreds of rows, each having only a few attributes), you will learn little.

I encourage you to pick an interesting topic and dataset (instead of a “safe” but boring topic) that would excite you -- this way, you would learn more. Be ambitious. It’s OK if you end up getting negative results, as long as you make the best decisions you can and you are satisfying all project requirements. One of the nicest thing of being a student is that it’s OK to try things out, so take advantage of this opportunity!

If you really need a rule-of-thumb guidance (for this course), I suggest you to consider datasets that have at least hundreds of thousands of rows/records, or at least hundreds of MBs (however, if that mostly contains "filler" information that you won't be using, then that's not a meaningful measure). Again, the larger the better. Use this project as a way to gain experience and knowledge in working with real datasets.

Unfortunately, I do not have permission to share previous project teams’ deliverables. Also, since all teams are welcome to choose topics most interesting to them, different teams' ideas and approaches can be quite different --- there are many different ways to produce good proposals. Based on the project description and guidelines, most teams in the past developed excellent projects. In academia, when submitting grant proposals, we are not provided with any examples. It is up to us to propose the topic, and to convince the proposal reviewers the significance of our problems, ideas and solutions. We are only provided with high-level format requirements and guidelines of our documents.

Below are two published articles that are based on previous projects from this course (campus section), the articles themselves are not project deliverables from this course, but are like extended, improved version of the teams’ final project reports. For our OMS students, these projects are mentioned in Week 1's "Course Introduction: Course Goals & Expectations" video, start at 4:16.

Aurigo: An Interactive Tour Planner for Personalized Itineraries

https://www.cc.gatech.edu/~dchau/papers/15-iui-aurigo.pdf

PASSAGE: A Travel Safety Assistant with Safe Path Recommendations for Pedestrians

https://poloclub.github.io/papers/16-iui-passage.pdf

To publish these articles, those student teams spent additional time and effort after the course has concluded to extend their project. For example, in Aurigo, the students design and conduct a formal controlled user studies; in PASSAGE, the students improved their methods of computing "safety" scores.

Proposal

Your proposal should answer Heilmeier's questions (all 9 of them; see list below); if you think a question is not very relevant, briefly explain why. In other words, your proposal should describe what you plan to do (the problem to address), why you want to do it, how you will do it (what tools? e.g., SQLite, PostgreSQL, Hadoop, Kinect, iPad, etc.), how your approach is better than the state of the art, why it may succeed, and when it does, what differences will it make, how you will measure success, how long it's gonna take, etc.

9 Heilmeier questions (source)- What are you trying to do? Articulate your objectives using absolutely no jargon.

- How is it done today; what are the limits of current practice?

- What's new in your approach? Why will it be successful?

- Who cares?

- If you're successful, what difference and impact will it make, and how do you measure them (e.g., via user studies, experiments, groundtruth data, etc.)?

- What are the risks and payoffs?

- How much will it cost?

- How long will it take?

- What are the midterm and final "exams" to check for success? How will progress be measured.

Your proposal document must be no more than 2 letter-size pages long, excluding references. Use at least 1-inch margin for each page (top, right, bottom, left). It must use 11pt font. The document must be in PDF format. You may create the document using any software that you want; we highly recommend using LaTeX (see below for example LaTeX template). Include any figures, charts, tables, captions, etc. whenever useful — they count towards the page limit (they may include text whose font size is smaller than 11pt, but such text must be legible). Your document should be self-contained. For example, do not just say: "We plan to implement Smith's Foo-Tree data structure [Smith86], and we will study its performance." Instead, you should briefly review the key ideas in the references, and describe clearly the alternatives that you will be examining.

- See other articles' related work sections for inspiration, e.g., Apolo paper

- Multiple papers may share similar themes, use similar methods so they may be summarized and discussed together.

- Note that survey account for 60% of proposal’s grade, so your survey should be substantial!

Grading scheme & Submission instructions

- 60% for the survey

- 30% for innovation

- 10% for plan of activities

- For every Heilmeier question that's not mentioned, deduct 5%.

- You may consider organizing your proposal based on the Heilmeier questions (e.g., each section addresses one question)

- Your survey should have at least 3 papers or book

chapters per group member (outside of any required reading for the class).

- Short papers, like PNAS, Nature, Science papers, count as 0.5.

- Copying the abstract of the papers is obviously prohibited, constituting plagiarism.

- For each paper, describe

- (a) the main idea,

- (b) why (or why not) it

will be useful for your project, and

- (c) its potential shortcomings, that you will try to improve upon.

- You may use any citation style (e.g., APA, Chicago). Google Scholar supports a wide range of citation styles; it also provides BibTeX (needed if your team is using LaTeX).

- Please make sure to cite your references in your survey.

- Clear problem definition: give a precise formal problem definition, in addition to a jargon-free version (for Heilmeier question #1).

- Provide a plan of activities and time estimates, per group member. List what each group member has done, and will do.

- Team's contact person submits a softcopy, named teamXXproposal.pdf, via Canvas (i.e., that person submits for the whole team), where XX is the team number (e.g., team01proposal.pdf for team 1)

- [-5% if not included] Distribution of team member effort. Can be as simple as "all team members have contributed similar amount of effort". If effort distribution is too uneven, I may assign higher scores to members who have contributed more.

Long papers refer to typical papers published at top academic venues (e.g., KDD, CHI, ICML). They are usually at least 8-10 pages long, in 2-column format, which translate into 5000 or more words. Thus, short paper would be 4-5 pages or fewer. Example long papers:

- GAN Lab. VAST’18. 2-column IEEE format

- SHIELD. KDD’18. 2-column ACM format

- ShapeShifter. PKDD’18, 1-column Springer format

They should be peer-reviewed, unless there is a strong reason for it not to be (e.g., a book chapter).

A paper that you read and cite can be relevant to your project in different ways. You are welcome to cite a paper if you can justify its strong relevance to your ideas, problems (e.g., motivate the urgent need to solve them), or approaches (e.g., your approach improves on an existing method). Searching on Google Scholar can also help you to find relevant papers.

Proposal Presentation

- 2 min per team. See the Piazza post for your team's presentation date and time. Presentations will take place during class time. First presentation starts at 4:30pm SHARP.

- If you overrun, we will boot you off the stage and deduct 5% of your presentation grade.

- Two teams can swap their presentation dates if both teams agree; no need to ask me for permission. Both teams MUST update the Google spreadsheet with the new dates.

- Attendance is mandatory. Lateness and absence will be noted; marks may be deducted for no-show. If you cannot attend, let me and TAs know through a private post on Piazza.

- If you team has a Q or Q3 students. You can choose to

- Present in class (physically, using the assigned time slot)

-

Submit a video presentation, called teamXXproposal.mp4 (or .avi or .mov) where XX is the

team number (e.g., 01 for team 1), through Canvas which shows your slides with voice narration. It is up to

you whether to show your face or not. If you choose this video option,

- You will have 3-day lag

- Please replace the date that I assigned to your group with the word "video"

- Every team's presentation slides will be collected via Canvas a few days before the proposal days, and pre-loaded to the computer at the podium, to reduce switching time between teams.

- Team's contact person submits the slides, as a file called teamXXslides.pdf (e.g., team02slides.pdf). PDF only; no PPT or other formats.

Grading

- [45%] You must answer the Heilmeier questions. 5% for each question. If a question doesn’t apply, say so.

- [15%] Brief literature survey. Can be combined with Heilmeier question(s).

- [10%] Expected innovation. Can be combined with Heilmeier question(s).

- [10%] Plan of activities

- [20%] Presentation delivery

- [-5%] Illegible text, tiny figures, bad color contrast, etc.

- [-5%] Overrun

- Your presentation does NOT need to strictly follow your project proposal document. For example, you can talk about ideas and materials that your team has come up recently.

- Points will NOT be deducted or awarded based on the number of presenters. We saw great presentations delivered by teams having various numbers of presenters.

Tips

- Use few slides. Less is more! Fewer slides mean less likely to overrun. Being succinct is hard.

- Practice timing and delivery! If you have several speakers, make sure you practice how to transition from one person to the next (e.g., passing the mic, passing control of mouse and keyboard, etc). PRACTICE! PRACTICE! PRACTICE!

Progress Report

No more than 4 letter-size pages (excluding references), 11pt font, typed. Use at least 1-inch margin for each page (top, right, bottom, left).

It mainly serves as a checkpoint, to detect and prevent dead-ends and other problems early on.

It should consist of the same sections as your final report (introduction, survey, etc), with a few sections "under construction", describing the work performed up to then, and the revised plans for the whole project.

Specifically, the introduction and survey sections should be in their final form. The section on the proposed method should be almost finished. The sections about experiments and conclusions will have whatever results you have obtained, as well as `place-holders' for the results you plan/hope to obtain.

Grading scheme & Submission instructions

- [70%] for proposed method (should be almost finished)

- [25%] for the design of upcoming experiments / evaluation

- [5%] for plan of activities (please show the old one and the revised one, along with the activities of each group member)

- Clear list of innovations: give a list of the best 2-4 ideas that your approach exhibits.

- Team's contact person submits a softcopy via Canvas (progress report only), named teamXXprogress.pdf, where XX is the team number (e.g., team01progress.pdf for team 1)

- [-5% if not included] Distribution of team member effort. Can be as simple as "all team members have contributed similar amount of effort". If effort distribution is too uneven, I may assign higher scores to members who have contributed more

Final Poster Presentation Peer-graded

Logistics

Presentation will start at 4:30pm SHARP. So arrive early, e.g., at 4:15pm. We plan to open the session up to everybody (College of Computing, etc.).- Each team creates a single poster for the whole team.

- Each student will present his/her team's poster during the poster session.

- Each student will have 3 minutes to present the poster, and 1 minute for Q&A.

- Thus, every team member should know his/her project very well, and be prepared to answer questions.

- Demo: optional but encouraged. Demo time counts towards the presentation time. If you decide to give a demo, please bring your own laptop. Assume there will little or no internet connection, and no ready access to power outlets.

- All team members must attend the poster session.

- If you cannot attend part of it, you must write to the instructors (via private Piazza post addressed to "instructors") at least 5 days before the presentation, or else you will receive a 0 for your presentation.

- Everyone is welcome to walk around to see other teams' posters, when you're not presenting or grading.

- Each student will also grade several presentations given by students in other teams during the poster session.

- Before the poster session, we will let each student know when he/she will present, and when he/she will grade others.

- Peer grading is NOT anonymous. That is, a presenter knows who the graders are, and a grader knows who the presenters are.

- If a grader does not finish all the assigned peer grading, that grader may NOT receive all or part of the grader’s own final poster presentation grade (i.e., up to 7.5% of final course grade), since the peer grading is an integral part of the project presentation.

-

We will compute a student's final poster presentation score as follows. For each rubric item, we drop the lowest

score, then take the average of the remaining scores. Then, we sum up these "averages" as the student's final

score. This formula should heavily suppress "outlier" scores. After the peer grading ends, as additional

safeguard, we will go through everyone's scores.

For example, suppose

for "What is the problem(no jargon)?", the student receives 4, 2, 3; and

for "Why is it important and why should we care?", the student receives 4, 4, 5; the final score is computed as:final score = sum(avg(4, 3) + avg(4, 5) + ... )

where "2" is dropped from "4, 2, 3"; and a "4" is dropped from "4, 4, 5".

I would like students to learn and practice delivering constructive criticism, for any concerns and weaknesses identified.

People rarely like to hear about negative comments, even if they are accurate and helpful. Giving negative news is always hard, but that is part of life! This means we should carefully phrase our comments as constructive criticism. For example,

- Instead of saying “too much text and not enough figures”, you could say "Fig 1 to 3 are important figures in this project; currently they are not easy to see (images are too small; text is not legible). Suggest reducing the amount of text, e.g., into succinct, bullet points to create space for the figures".

- Similarly, avoid "I don't think that the visualization is anything new or how it is helpful," which is highly subjective. Instead, justify your comments; if the presenter did not clarify the novelty or significance of an approach (it is probably new, but just that the presenter did not point it out), you could say "it's unclear from the presentation and poster whether the proposed visualization is an improvement over the state of the art (it seems to be a standard design); more clarification is needed."

Poster Design

Design and print the poster *well before* your presentation day, to avoid last-minute rush.The poster must be in portrait orientation, 30 inches wide and 40 inches tall. Foam core poster boards, push pins, and easels will be provided to you to mount the poster. We suggest 18pt font size and larger.

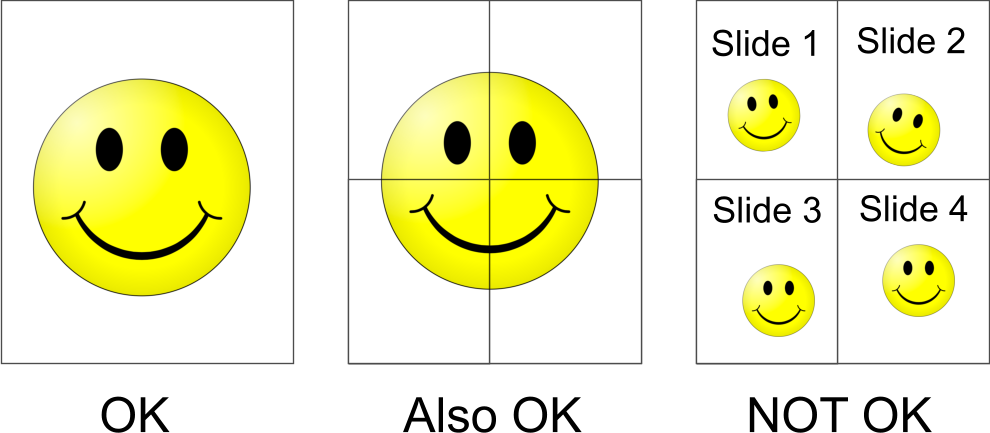

A deck of PowerPoint slides is not acceptable as a poster. However, you may print your design on multiple smaller sheets of paper and then carefully stitch them together. See the illustration below for what is allowed and what is not.

Your poster presentation should cover the following parts (point distribution shown on the left). Thus, the grading is about both your presentation delivery (e.g., what you say, where you direct the audience’s attention), and the poster content.

If you overrun, besides losing points for the rubric item “5% Finished on time?”, you may lose additional points for the required content that you have not covered within the time limit --- imagine you are delivering a presentation in person and you are alloted 3 minutes, once that time is up, you would need to stop and would not be able to present additional content (thus, that content will not be graded).

| 10% | Motivation/Introduction:

5% What is the problem (no jargon)? 5% Why is it important and why should we care? |

| 20% | Your approaches (algorithm and interactive visualization):

5% What are they? 5% How do they work? 5% Why do you think they can effectively solve your problem (i.e., what is the intuition behind your approaches)? 5% What is new in your approaches? |

| 10% | Data:

5% How did you get it? (Download? Scrape?) 5% What are its characteristics (e.g., size on disk, # of records, temporal or not, etc.) |

| 25% | Experiments and results:

5% How did you evaluate your approaches? 10% What are the results? 10% How do you methods compare to other methods? |

| 10% | Presentation delivery:

5% Finished on time? 5% Spoke clearly and at a good pace? |

| 25% | Poster Design:

5% Layout/organization (Clear headings? Easy to follow?) 5% Use of text (Succinct or verbose?) 5% Use of graphics (Are they relevant? Do they help you better understand the project's approaches and ideas?) 5% Legibility (Is the text and figures too small?) 5% Grammar and spelling |

- Present in class, physically

- Submit individual 3-minute video presentations (one presentation per student) through Canvas via the entry

“Poster Video - Q”.

The standard 3-day lag applies.

Name each video recording teamXXposter-YY.mp4 (or .avi or .mov), where XX is the team number (e.g., 01 for team 1), and YY is the student's last name (e.g., smith).

Grade period is NOT available for this video presentation submission, since on-campus students cannot use grace period either (they all present on the same day).

Your video should show your poster (e.g., as pdf on your computer screen via screen capture, say using Quicktime, MonoSnap, etc.) with voice narration; it is up to you whether to show your face. You should be able to create this recording quickly with little effort – no need to do any special video or audio editing. You may zoom into and out of the poster as you present, so the viewer can more easily see the poster content.

Possible software to create posters

- Powerpoint/Word (save as pdf) -- GT's Office365 Powerpoint supports collaboration.

- Apple Pages (FREE) supports real-time collaboration (via iCloud and desktop software)

- Inkscape (free, cross platform)

- Polo uses Affinity Designer (Mac and windows)

- Adobe Illustrator is pretty good and available for limited trial and also installed on Library Mac Mini.

- Google Drawings (File > Page Setup to set document size)

- draw.io (File > Page Setup to set document size)

Where to print posters?

- Paper and clay. http://studentcenter.gatech.edu/seedo/paperandclay/Pages/default.aspx

- Poster printing is available for free at the GVU, but you have to physically go to the machine, log in, and upload your pdf http://gvu.gatech.edu/wiki/index.php/Poster_Printing_FAQ

- Poster printing is also available the library http://librarycommons.gatech.edu/lwc/multimedia.php

- PCS - more expensive http://www.oit.gatech.edu/rm/service/print-copy/print-and-copy-services

Example posters

Final Report

It will be a detailed description of what you did, what results you obtained, and what you have learned and/or can conclude from your work.

Components:

- Writeup: no more than 6 letter-size pages (excluding references), 11pt font, typed. Use at least 1-inch margin for each page (top, right, bottom, left). Describe in depth the novelties of your approach and your discoveries/insights/experiments, etc.

- Software: packaging, documentation, and portability. The goal is to provide enough material, so that other people can use it and continue your work, if you are to open-source it -- in other words, you should make it easy and attractive for others to use your work.

Grading scheme & Submission instructions

- Writeup

- [2%] Introduction - Motivation

- [3%] Problem definition

- [5%] Survey

- Proposed method

- [10%] Intuition - why should it be better than the state of the art?

- [35%] Description of your approaches: algorithms, user interfaces, etc.

- Experiments/ Evaluation

- [5%] Description of your testbed; list of questions your experiments are designed to answer

- [25%] Details of the experiments; observations (as many as you can!)

- [5%] Conclusions and discussion

- [-5% if not included] Distribution of team member effort. Can be as simple as "all team members have contributed similar amount of effort". If effort distribution is too uneven, I may assign higher scores to members who have contributed more.

- [10%] Team’s contact person submits one zip file, called teamXXfinal.zip, via Canvas, where

XX is the team number (e.g., team01final.zip for team 1). The teamXXfinal.zip will contain the following 3

components:

- README.txt - a concise, short README.txt file, corresponding to the "user guide".

This file should contain:

- DESCRIPTION - Describe the package in a few paragraphs.

- INSTALLATION - How to install and setup your code.

- EXECUTION - How to run a demo on your code.

- DOC - a folder called DOC (short for “documentation”) containing:

- teamXXreport.pdf - Your report writeup in PDF format; can be created using any software, e.g., latex, Word.

- teamXXposter.pdf - Your final poster.

- CODE - All your code should be added here. Make sure that your package includes only the absolutely necessary set of files.

- README.txt - a concise, short README.txt file, corresponding to the "user guide".

This file should contain:

Should datasets be included as part of our submission?

If you are referring to (small) toy data for a demo (that we/TAs will run), you are welcome to include them. Think about the open-source software libraries that you have seen or have used, they would often include some sort of "quick start" guide to get a demo running on a toy dataset.For large datasets, please do not include them; if the dataset is public and can be easily downloaded, include the link to the dataset.

If getting a dataset requires writing scripts/programs, include those scripts, and write down the steps that people will need to go through (e.g., register for an account to get API key).

If you have processed the dataset in some ways, include the code you used, and the steps people will need to go through.

Georgia Tech Create-X opportunity

Georgia Tech as one of the top universities in entrepreneurship is the home to one of the most successful incubators called Create-X. All Georgia Tech students can apply for the Startup Launch Create-X in Georgia Tech. If your team works on a good idea and you would like to take the next step and commercialize your idea and start your own company, I strongly recommend to apply for the Startup Launch in Create-X and take advantage of Funding, Coaching and many more supports that come with this program.